Chris Fisher is the founder and co-director of The Earth Archive initiative — an ambitious scientific project aiming to scan the Earth’s entire surface before it’s too late.

Chris is an archaeologist and a professor at Colorado State University. He is an accidental geospatial person. In 2009, he was tending to his archeological fieldwork in Mexico — a new settlement no less — when he realized he needed a fresh way to document thousands of building foundations.

He turned to LIDAR and never looked back.

WHY DID YOU NEED A NEW WAY OF DOCUMENTING THINGS?

Technically, there is nothing wrong with the way people have been doing it for years. It’s still viable.

But it’s time-consuming.

And slow.

There were so many building foundations at this site in the central Mexican state of Michoacán. Walking across the landscape with teams of people manually annotating house foundations would have taken over a decade, in my estimate.

I’m notoriously impatient. I didn’t want to do that.

There had to be a better way to do this, and there was.

A technique called airborne LIDAR.

HOW WAS LIDAR GOING TO MAKE A MASSIVE DIFFERENCE?

I walked down the hallway to a colleague’s door, and said, “Dude, there’s got to be a better way to do this.”

Something faster, more accurate, and something that gives us a visual of what the entire landscape looks like.

It’s easy to find individual features. But putting the complete picture together is challenging when you’re in an area with a complex topography and a lot of housing foundations, as with that site.

We decided on a new technique called LIDAR. Another team of archaeologists had just used it with impressive effect at the Maya site of Caracole. We had the resources, and we found a company willing to fly the LIDAR for us.

WERE YOU EXCHANGING ONE PROBLEM FOR ANOTHER? NOT SEEING ENOUGH TO SEEING EVERYTHING?

Initially, before we knew how to wrangle the point cloud data, we spent a few months scrambling to figure out what to do with it.

The data is at such a high resolution that we can see all individual house foundations. The data quality is so much better than we could do by hand that it was a no-brainer to use the LIDAR instead.

Seeing the whole site is, in some respects, a new theoretical problem versus seeing the individual features only. But the great thing about using that kind of LIDAR data is that everything is recorded in perpetuity once you fly it. The point cloud data doesn’t degrade like a photograph. People can always go back and redo your work with LIDAR.

That’s not possible using traditional archaeology and traditional surveys.

IS THIS A TOOL FOR COLLECTING PHYSICAL FEATURES? OR CAN YOU ANALYZE THE CIVILIZATIONS’ CULTURES AS WELL?

We can see building foundations and site layouts.

We can identify where sites are in the landscape and pinpoint landscape features, such as roads, agricultural terraces, all of that.

The real trick is connecting that to the actual people that made those features.

Archaeology is a crazy science because the people we study are dead.

In an ideal situation, we’d have a time machine. We’d go back, hang out and talk with those people and live with them. The same way that a cultural anthropologist would learn the language and then ask people questions about how they organized themselves and how they came to be.

But we can’t do that because those people are dead. We use proxies for their behavior. Archaeologists have long used patterns of human land use to comprehend human behavior. We’ve developed theoretical mechanisms and ways of thinking about the past’s people and artifacts to understand human behavior.

Artifacts are proxies for human behavior. A building foundation is just another kind of artifact, but it’s difficult to make sense of. That’s why we spend so much time in school figuring that stuff out.

WHAT DOES THAT HAVE TO DO WITH THE EARTH ARCHIVE INITIATIVE?

As I worked on this Mexico project that used LIDAR to look for a scientifically unknown culture in central America, I came to many realizations.

To field verify the LIDAR results, we had to enter remote places via helicopter where no modern people live.

There’s evidence people haven’t been in this place for centuries. I’ve done fieldwork worldwide, but this was the only place I’ve been to where there wasn’t any plastic.

That’s how remote it was.

The experience transformed my thinking about the Earth and how fragile it is. After we were there, we could immediately see our impact — a landing zone had to be cleared, and some garbage had to be hauled out that was previously left there (*not by us.)

This place had to be protected.

One of those light bulbs appeared over the top of my head. This is like a microcosm of what’s happening globally with the climate crisis and dramatic earth system changes. We have a limited time to record the Earth as it exists now for future generations.

I realized we could use LIDAR to create a permanent digital record of what the Earth’s land surface looks like today to preserve it for future generations.

That’s the kernel of The Earth Archive initiative.

ARE YOU COLLECTING LIDAR FROM DIFFERENT GEOGRAPHIC AREAS AROUND THE WORLD AND STORING IT SOMEWHERE? OR IS IT MORE THAN THAT?

As an archaeologist, I spend hours practicing digital deforestation; removing vegetation from these point cloud data to see the archeology below.

All the information I’m filtering and digitally turning off are the careers of hundreds of other scientists who study tree size, age, species, geology, hydrology. The list is endless.

Airborne LIDAR records are the ultimate conservation records. Our goal is to scan the Earth’s entire land surface — all 29.2% of it — within the next decade.

Before the changes we’re experiencing because of global warming and everything else that’s happening become so dramatic, the Earth will have changed.

We have a limited time.

Many first-world countries are already completing these scans. Such as several European countries or the 3DEP program in North America, though the resolution isn’t as high as what we’re asking for.

We’re focusing our initial efforts on threatened areas and places that may not have the resources to do these kinds of scans.

WHAT ARE SOME OF THOSE AREAS? HOW BIG ARE THEY? WHAT KIND OF CAPITAL DO YOU NEED TO ACHIEVE THIS?

The areas involved are massive. Some people have called this a crazy idea. It is an entirely crazy idea.

This entire project started over a beer with my colleague.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could scan the entire surface of the Earth?

We laughed and had a couple more beers. Suddenly, it didn’t seem like such a crazy idea anymore.

We’re facing massive problems and we need big solutions. This is one potential solution.

Some of the most threatened areas are the Amazon, Central America, parts of Africa, and parts of Southeast Asia. Our initial scan will focus on scanning the entire Amazon Basin. It’s massive, and it will cost a lot of money — about $20 million.

We think we can do it in about five to six years. It’s a massive logistical effort. Amazon encompasses nine countries — requires a lot of permissions and partnerships, but we’re in the process of building those.

We’re likely to begin scanning in the middle of this summer, 2021.

WOW. ISN’T ALL THAT DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS PROBLEMATIC?

The biggest problems are not tech-related — tech problems always have tech solutions and people who want to resolve them.

The biggest problems when doing any kind of fieldwork, especially for the Earth archive scans, are the social and political issues. They take up the most time.

When we first started this, I thought one major bottleneck would be the size of the files and computers we need to unpack the data and analyze it.

Interestingly, the bottlenecks are not necessarily where you might logically place them.

One place is data storage and moving data from the aircraft to the place where it’s initially analyzed and processed. We work with Seagate and their new system called Lyve, a shuttle data service to resolve some of that.

WHAT ARE THE CULTURAL AND SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF MAPPING AREAS LIKE THIS?

People will see deforestation and expose countries that might cover it up.

Yes, and we’ll do the best we can with sensitive information.

You can already follow deforestation using satellite imagery. There was a scandal early in the Bolsonaro Administration at the Brazilian Space Agency’s scientific arm, INPE; someone was fired for pointing out just how much illegal deforestation had occurred.

We think we’re going to be okay as we’re initially focusing on areas slightly outside of the deforestation arc within the Amazon — we’ll see how that goes.

It’s a sensitive issue and we’re sensible.

Another thing going for the Earth Archive is that we want to open-source all the data and make it publicly available for free.

To do that, we’re building Commissions in each of the nine countries to figure out the best ways to release the data. There will be representatives from stakeholder groups on those Commissions, including indigenous groups, academics, NGO members, and governmental officials.

We may not release some data immediately. I’m an archaeologist and I know this — in long timescales, as the data ages, it becomes less sensitive. If we hit something especially sensitive, we won’t be able to release the data for several years.

From my perspective, that’s still open sourcing, although obviously, the best-case scenario would be to release it immediately.

WHAT SENSITIVE THING DO YOU THINK YOU MIGHT UNCOVER? ARCHAEOLOGICAL OR ECOLOGICAL?

Both.

It could be an indigenous site where people don’t want the location of that site released. An uncontacted group of people, for example.

The Amazon is one of the last places on Earth where there are uncontacted people — they’re uncontacted because that’s their desire.

I can’t blame them, and we need to honor that.

We’re developing ways to ghost some of those sensitive areas out of the data before it’s released, in the same way, that, for example, in the United States the 3DEP program goes out in collaboration with indigenous groups and first nations groups. 3DEP cuts out culturally sensitive sites from the data they release.

ARE YOU SURPRISED BY THE CULTURAL CHALLENGES THE PROJECT IS FACING?

I’m surprised by some things, but not totally blown over.

As an archaeologist, I’ve run extensive projects internationally, especially in Mexico. The hardest part of running a big archaeological project is not technical.

It’s not doing the excavations, nor doing the artifacts. It’s not collecting the data either.

All I do is governmental permits, community permissions, sorting housing, getting the right peanut butter for students so that everybody’s happy and perform to their optimal ability in the field.

When we’re on big projects, I don’t do any archaeology. I have more fun visiting my friends’ excavations because I just get to hang out and do some archaeology.

Some of the biggest challenges we have are things we never expected, like sourcing vehicles for excavation fieldwork. In Mexico, this is incredibly difficult and expensive. It takes a lot of time and effort just to get the vehicles.

WHAT PROBLEMS COULD THIS MASSIVE DATA SOLVE ONCE IT’S AVAILABLE TO EVERYONE?

We can immediately show some really cool stuff for the Amazon.

For example, there’s a debate among Amazonian scholars about how many people were in the Amazon at the time of European contact. As soon as Europeans arrived in the Americas, the indigenous populations were decimated by European introduced disease. Some estimates are nine out of every 10 people.

A rate like that is much higher than the current pandemic death rate.

Yet, look how disruptive COVID has been in such a brief space of time.

Can you imagine a 90% death rate? It’d be like Stephen King’s The Stand. That’s the nearest analogy I have.

Because of that, we don’t know how many people were in the Amazon or what their environmental impact was. So there’s a debate among Amazonian scholars whether the Amazon is really an abandoned garden, which is what most archaeologists believe, myself included, or the Amazon was lightly affected by people, and it’s mostly a natural ecosystem — an ecosystem that existed without human impact for most of the time, up to European contact.

With the data, we could immediately resolve this debate. Boom. Done. We can see the archaeological sites on the ground, the road networks, the landscape features, terraces, fish ponds, all that sort of stuff.

But then that has some serious implications on how we think about the Amazon and how we move forward with protecting it. We could also get intensely accurate deforestation measurements and pair our high-resolution record with coarser records to answer various questions about deforestation’s historic nature.

We could look at changing water budgets. It would be the most accurate way to measure carbon budgets, plus a host of other things.

We also expect that as computing power increases, and with AI and other technologies, people will go back through the Earth Archive data asking questions and using future technologies we can’t even imagine today.

A host of synergies will come together to do these analytics beyond what we can even think about now.

WHAT OTHER AREAS ARE ON YOUR LIST?

We’d like to scan Central America.

There’s already a lot of scanning happening in the Maya region in Mexico. Still, there’s a lot more that would need to happen.

Once we get the Amazon scan going, next is Africa. We’d love to do a discontinuous transect starting in Egypt and ending in South Africa — down the eastern part of the African continent. That would be a mind-blowingly massive undertaking.

It wouldn’t be a continuous transect — it would be discontinuous. We’d move back and forth a bit East-West to take advantage of some of the most spectacular and culturally and ecologically important areas.

That is a scan that’s being discussed and planned.

HOW IS THIS GOING TO BE USED? IN AN APP? IN A BROWSER?

We’ve been lucky to partner with VoxelMaps.

They have a fantastic platform and interface — a voxel that starts as a three-dimensional pixel. From the center of the Earth moving outward, encompassing the Earth and beyond.

Each of those voxels is nested and numbered individually. They have a browser allowing you to look at 3D data — or rather 4D because each voxel can hold unlimited amounts of time information.

It’s a 4D platform with a web browser to browse through the LIDAR data. View it at a very high resolution, which we’re determining right now, grab an area, download it as a DOS file, or perhaps something else.

A voxel environment looks a lot like Minecraft. It’s an absolutely incredible analytical space we can take advantage of with VoxelMaps.

DO YOU EVER SUFFER FROM IMPOSTER SYNDROME? WHO AM I TO SCAN THE ENTIRE SURFACE OF THE EARTH?

Yes. All the time.

This is the scariest thing I’ve ever done. It could fall completely flat on its face.

I don’t think it will.

But I’m all in. We have to do it because it’s so necessary.

It makes so much sense to me.

We have better 3D maps of the Moon than we have our own planet. How can that be?

I hope I will not be the laughingstock and fall on my face. I’d have to go to Alaska and build a cabin and live there forever in that case. It would be so embarrassing.

But I persevere.

CAN PEOPLE CONTRIBUTE? HOW AND WITH WHAT?

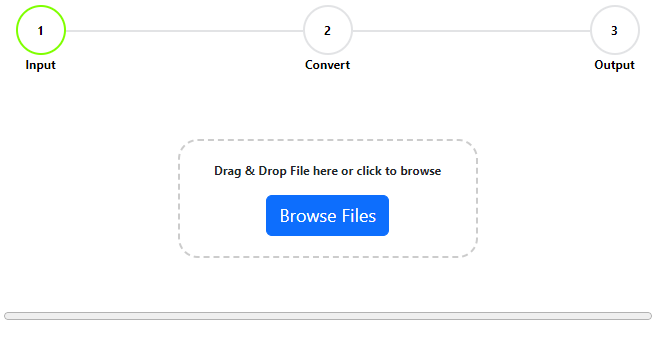

We’re looking for all sorts of help. If anyone has any ideas, there’s a contact form on our website.

The best help we can get right now is financial. We’re holding a massive Virtual Congress on 15-16 June 2021.

There’s also a Kickstarter campaign at the end of February 2021. Those funds will go directly to the Amazon campaign.

Although the COVID situation may delay us a little, we’re ready to start scanning in the Amazon — we have the permissions and the connections to begin in Brazil and Colombia. We hope to do that by the middle of this summer, 2021.

————————————-

Chris talked a lot about the Amazon and I want to mention Google Earth Engine here.

If you go to Earth Engine, you can see change happening. It’s a fantastic resource. If you’re in doubt that change is happening, and things are moving faster than what we imagined, go along and see it for yourself.

On the left-hand side, you’ll see a list of pre-selected areas. Click on one of them and you’ll see how change happened over the last 30 years.

It’s an absolute pleasure to talk to people like Chris — people who take on ambitious projects, not because they believe they’re the perfect candidate to lead the project, but because they see something that’s broken, and they decide to fix it.

Chris and his colleagues’ leadership show that the Earth Archive project isn’t getting the attention it deserves.

When I asked Chris if he ever suffers from imposter syndrome, it was an immediate and obvious “YES.”

But in the same sentence, he also said, but he’s all in.

It’s not because he believes he’s the perfect candidate for this project or the only person to solve this problem.

He’s all in because he sees an opportunity to make things better. He sees a problem that needs to be fixed, and it’s more important that it gets fixed than who does the fixing.