Our guest today is Hans van der Kwast, a physical geographer and GIS and remote sensing lecturer. After furthering the field through a number of research positions, he now is the Senior Lecturer at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education.Holding special interest in geospatial technology as it relates to water resources, he places a high priority on the dissemination of knowledge for the sake of improving our planet.

In Person vs Online Geospatial Education

As has become apparent to many during the COVID-19 crisis, there are pros and cons to both in person, and online education. The physical environment is the most noticeable shift on the surface, but the effects of this percolate through many supporting elements of a curriculum, from the perspective of both the students, and the teachers.

In person education facilitates instant communication with participants, and allows more organic growth of discussion topics in the classroom as challenges are encountered. It can be easier for students to ask questions of the lecturer, as well as for the lecturer to keep an eye on student progress and check for mistakes, or deviations from the intended workflow. The emotional and community connection that comes with being physically in the classroom can be replicated online with the right personalities.

The structure of an in person course, however, does not directly translate to the online environment.

Online courses have taken the world by storm in recent years, but this does not mean digital coursework is a new science. For years, teachers have been experimenting, workshopping the system to best take advantage of the unique resources the internet provides. The modularity of online coursework is a particularly useful benefit of the medium.

Lecturers can focus each module on the discrete elements of the topic at hand, then bundle together modules into full courses,

workshops, or programs to best serve the audience they are selling to.

Popular platforms to facilitate online learning are Zoom, Microsoft Teams, BigBlueButton, and Moodle.

Online learning has the benefit of scaling well. Far more students can be hosted online than can be served in a physical classroom. Experience has shown that students generally are more self-sufficient in an online environment as well.

Students are more likely to research a question or issue themselves before reaching out for assistance,

rather than simply raising their hand for simpler questions, like how to find their data, or unzip a file. Some of the shortcomings of online learning are screen fatigue, technical problems and the tendency to lose interest in unengaging screen recordings of live lectures if a course is not well-designed.

Driving Online Course Engagement

In order to serve out an engaging online geospatial course, the lecturer must pay close attention to how they design the course. The traditional style of real time courses does not convert directly to online. Recorded presentations, PowerPoint slide decks, and live Zoom lectures work well in an emergency situation, like a rapid shift online due to a global pandemic, but they are not a viable long term option for successful remote learning.

Variety is the spice of life, but it is also the secret sauce for high course engagement.

The course should be as interactive as possible to ensure that students are absorbing and understanding the content presented.

This means experimenting with, and taking advantage of all the tools and methodologies that have been developed thus far.

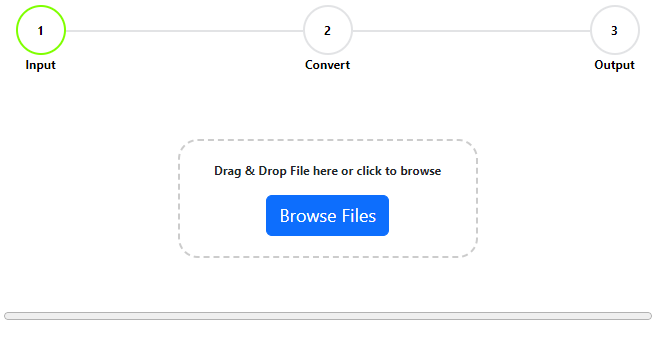

As far as effectively structuring a course, the modular nature of online coursework lends itself well to GIS. A module may begin with some videos providing an overview of the concept to be explored. These may be followed with a short quiz to check the viewer’s comprehension of the video content. A good next step is a hands-on assignment in GIS software (ArcGIS, QGIS, Google).

This workflow may be guided step-by-step, but is best paired with an overviewing flowchart of the workflow to help the student better conceptualize the structure of what they are doing. Throughout the workflow, checks should be provided to make sure the students cannot deviate too far from the intended workflow. Are they using the right projection? Are their selections accurate? Etc. Finally, an assignment on the topic may be completed, and submitted for grading.

Keeping students engaged throughout the module can be done by employing tools like H5P, or Kahoot.

The H5P plugin allows teachers to inject interactivity into their courses in a variety of ways.

These include multimedia timelines, layering interactive content onto videos, and many more activities you can integrate into an HTML5 page. Kahoot also makes learning fun by creating live group games out of your content (think educational Jackbox).

Geospatial Education as a Business

Although many educators enter the profession for the joy of sharing knowledge, there are still bills to pay, and creating courses is a significant time investment. There is a huge market for online courses that many have already entered. This makes it all the more important to understand your audience if you hope to succeed in creating a course of your own.

There are three main types of students you will likely encounter in an online course.

The first are masters students, who likely have great personal interest and stakes in the course being offered. Another group are private individuals who have funded course participation themselves in order to advance a specific goal they have. Both of these types are likely to be motivated, and engaged throughout the course.

The final type of students are working professionals, who have had their training funded by their organization. Commonly, these students will be less engaged than others, and will require some additional interaction to ensure they effectively complete and absorb the course materials. Large group meetings and live discussion can help engage students and enlighten them to the simple fact that GIS is a lot of fun.

Learning to accommodate all backgrounds of students widens your audience, and increases the chances that former students will share their experiences, contributing to word of mouth growth.

Monetizing knowledge can be an intimidating task. There is plenty of content accessible for free on the internet, why would someone pay for it instead? The answer is accountability, and structure. Some people are perfectly capable of navigating a new subject from scratch themselves, but others turn to platforms like Coursera, LinkedIn Learning, or Udemy to be guided through a topic. The truly asynchronous nature of these planned courses allows lecturers to manage many more students than would be possible through synchronous learning, without the costs of maintaining a physical classroom.

Again, taking advantage of the modular structure associated with online learning can be of great benefit here.

Lecturers can piece together courses that appeal to a wider range by mixing and matching different modules into cohesive courses.

They can even monitor success and completion rates through built in platform tools, or other common tools like Google Analytics.

An encouraging fact: Course participants that paid for a course, rather than accessing it for free, are far more likely to complete the course.

This is even more true if there is a certificate on the other side. If your love for GIS learning extends outside the 9 to 5, consider adding online courses in any of their forms to your future.