Ariel: And I got to this point where I was like, “Jeez. Like what if we could build out tools that would actually dramatically lower the costs of data collection, data acquisition at a global scale?”

Daniel: Hi, my name is Daniel, and welcome to The MapScaping Podcast. This is a podcast about companies and individuals that are doing incredible things in the geospatial world.

Daniel: Today I’m talking to Ariel. Ariel is the founder of Hivemapper. Hivemapper is a system which lets you upload video footage to the cloud which is then automatically processed into usable geographic data and has a whole bunch of uses. It’s a really interesting technology, and it is definitely scalable. I hope you enjoy the interview.

Daniel: Well today I’m talking to Ariel, and he comes to us from Hivemapper, and they’re doing something really interesting over there. But first, could you just tell us a little bit about your background, Ariel?

Ariel: Sure, sure. So I started off in the mapping world when I was in Yahoo. So Yahoo Maps, Yahoo Search, we looked up and realized that about 20-35% of our queries were all local mapping address related, and so there was a very very strong push to dramatically improve all of the mapping local related queries for Yahoo Search, and so I got very deeply involved and fell in love with local and maps from that entire process about … Jeez now like more than ten years ago.

Ariel: And what I started to realize was just how inordinately expensive it was to create maps, to create local information. But more importantly, to create it fresh and maintain the freshness associated with this data at a global scale. And you know, frankly, I would go to the Yahoo exec team and start to make these pitches for, “Hey, we need to invest in massive amounts of data.” And I continuously got knocked down. It was just like the types of prices that we were talking about and the types of costs was frankly just too much for them to stomach, and that was just deeply frustrating because I could see how much some of our competitors like Google were investing in this.

Ariel: And I got to this point where I was like, “Jeez, like what if we could build out tools that would actually dramatically lower the costs of data collection, data acquisition at a global scale?”

Ariel: And so it was just around that time that the iPhone and the Android got going, and I said, “Well why don’t we turn all of these devices that people now have that have cameras that have great input mechanisms as basically this mobile smartphone army of data collectors?” And financially incentivize them to go around and update maps and update this information for us? Rather than do it at Yahoo, I started a company called Gigwalk to do exactly that.

Ariel: And we very quickly signed up most of the major mapping companies that they would put in what we refer to as little gigs. You know, pay somebody $2 whether or not the stop sign had been updated. Pay somebody $3 to go in this neighborhood and update all the one way streets. And this was about 2010, and we very quickly started to grow. Hundreds of thousands of gigs in the system. All these kind of people doing these gigs, collecting those data. And that business started to, at some point, kind of hit a wall frankly where just the number of customers that we would have globally was relatively small, and so we then expanded out to other verticals and it kind of grew from there.

Ariel: But at a certain point I was like, “Hmm, you know what? I think there’s maybe fundamentally an even better approach to solving this problem of how do you create maps and refresh them at scale?” And so that’s when we started Hivemapper. So Hivemapper takes video, ultimately lidar can automatically build maps from any moving video camera and builds those maps in three dimensions, but more importantly, in addition to just building the maps, it tells you what’s changed. So it tells you there’s no longer a street sign here. This building has been destroyed, and there’s a new construction project, and that construction project is now … Has a new building there at 30 feet tall. It can tell you the terrain has changed.

Ariel: So fundamentally, it’s taking this idea that there are all these video cameras ultimately all these lidar sensors out in the world, and how can we ingest all that data from all these new sensors and put it to use? Right? Put it to use in terms of really helping people understand how our physical world is changing, and then how that impacts them whether you’re in the logistics business, whether you’re in the intelligence business, whether you’re in defense, whether you’re a local city planner or operator. Whether you’re in oil and gas. There are just hundreds of different use cases, and we could talk about some of those.

Ariel: So that’s my journey so far over the last ten or twelve years.

Daniel: It sounds really impressive. It sounds like that … What was it, Gigwork you called it?

Ariel: Gigwalk.

Daniel: Gigwalk.

Ariel: So you would walk to gig.

Daniel: Yeah, it sounds like you invented the Mechanical Turk of mapping there.

Ariel: Yes, it was kind of the mobile Mechanical Turk that we definitely got … when we’re explaining to people, if you knew what Mechanical Turk was, it was oh okay so you guys are like the mobile version of that. And so I think that was like a pretty good pivot for people from a mind’s frame perspective.

Daniel: And like if we could just go back into that for just a second there. The problem with that was that you couldn’t … there was a limited number of people interested in that kind of data, or was it hard to have enough people to update the data? And that’s why you moved onto DIVIDIA? To other sources?

Ariel: Yeah, great question. So I think there was a couple issues. One is the fundament that I think it was a customer issue, right? The number of people that would pay for just raw data was maybe like globally $40-50 million of recurring revenue. So what would happen is you spend a lot of time getting a customer, they’d be like, “I love this. I have this project. This is great.” And then they would spend, I’m just gonna make … You know, $50,000 on a project, and then they’d go away for like 18 months and the come back with like another $75,000 project.

Ariel: So to get them into some sort of annual package where it was recurring revenue, that was a big challenge for us.

Daniel: Yeah, yeah. So then you moved onto Hivemapper, and you talked about using cameras, video cameras especially. And you talked about using cell phones as well. I might be mixing the two things up there, but anyway video cameras was a hugely important to Hivemapper. Is this any kind of video camera? Is it a [Blink 00:07:25], does it have to have geotags? What’s the requirements?

Ariel: Yeah, so we started off with cameras from drones initially. So that was like the very very first version of Hivemapper which was drones kind of have this nice perspective on the earth. You can orient their camera looking down. So the camera does have to be moving, and the camera needs to be looking at the angle at a movement. So let’s say it’s a drone or an airplane, you want to be like 45 degrees off a [nader 00:08:02], roughly.

Ariel: And the thing that’s also pretty challenging in terms of the technology is if the camera’s moving around aggressively, right? Like it’s panning there, it’s zooming there. That makes it harder to actually build a nice consistent map. So there’s definitely things that you can do from a collection perspective that improve the quality of your map, and we try to provide people.

Ariel: But we’ve also seen situations where somebody uploads a video. It’s a longish video like 20-30 minutes, and of that there’s maybe only five minutes that are actually mappable, so we are able to like automatically determine, “Oh that 25 minute video, here’s the five minutes that are actually like high-quality map, and then we just kind of discard the other 20 minutes.”

Daniel: As drones, the technology around drone mapping is improving day to day, I would imagine, and I’m assuming that there must be some sort of standards involved now. That there are some international standards. “Hey, when you shoot data from a drone, then it comes in this format, it has the standard …” Are all these things, are they helping you or are they sort of divergent? Is everybody making their own standards, their own formats, their own sort of technology for drone mapping?

Ariel: Yeah so those standards definitely help. There’s no doubt about that. That the metadata that comes with a video, for example. So whether you’re flying a drone at 15,000 feet or flying an airplane or flying a commercial drone at 400 feet, there are a set of standards in terms of the metadata that’s coming off of those drones, or more importantly, coming off of those video cameras.

Ariel: And so we’re able to ingest the video and then also extract out all of the metadata that comes with that video, and that’s very helpful in terms of just orienting Hivemapper to, “Oh, okay. This was captured at this part of San Francisco at this time of day, and this was the kind of camera that was being used.”

Ariel: So all of that metadata is definitely extremely valuable and extremely useful in terms of assisting our technology to build high-quality maps. So yeah, no doubt about that.

Ariel: I would say that fundamentally, the problem with the commercial drone industry right now is that you can only fly these things for fifteen, twenty, thirty minutes at best. And that’s just not … You’re not gonna build a very significant map so what you have is this problem of somebody flying a drone at 15-20 minutes, and then it’s like, “Ah, Jeez. I gotta bring it back down, swap the battery,” you know, then do that entire thing again.

Ariel: And so what we’ve seen is is that in terms of actually building maps and doing that at scale, things like higher flying drones that obviously the military and intelligence operations use, as well as airplanes, just can cover a ton more ground and oftentimes do that even more cost effective than a commercial drone just because of the limited flight time that those things have today.

Daniel: And those, the higher flying vehicles, they’re still providing the same resolution or better maybe?

Ariel: It depends. So it depends on, what type of camera they have. Some of the cameras that are flying on those airplanes and these higher flying drones are exquisite. You’re talking about cameras that are each $250,000 to $500,000 a pop. If you look at some of these kinds of military drones, the most expensive piece of equipment on those drones is by far the video camera.

Ariel: And so yeah, you can get some amazing resolution on those with a great zoom. It does limit kind of how you can fly and so forth. But fundamentally, we’ve seen … There was actually a map on our website that you can check out which was captured with an aircraft flying at 15,000 feet over the Chevron refinery here in the San Francisco Bay area, and the map is fantastic. It georegistered to our map at roughly 35 centimeters accuracy. So that just gives you a sense of just how good of quality a map you can build and the kind of accuracy that you can achieve from a higher flying aircraft.

Daniel: That was actually one of my next questions. Like I’m fascinated by this idea of using video as an input to a map. Like we’re all used to maps being static. So the idea that video, like a dynamic thing, can turn into this sort of static map and be updated so frequently. And even the idea that the metadata isn’t … I mean, it sounds like it’s not necessary as such. It sounds like it’s good to have and nice to have but not necessary. So I think that’s amazing, that side of it, but yeah so it leads differently into some questions around accuracy.

Ariel: Yeah so if 35cm is kind of the definitely right now without using any sort of ground control points, just the video, we can achieve 35cm, and there are ways to improve that and get that down even further. You know, the number of use cases that exist where the requirements are like for five or ten centimeters definitely exist. You know, construction world etc where you’re looking at very, very precise measurements that you need. But there’s a ton of use cases where it’s like yeah, 35cm, that’s like so much better than satellite. So much fresher than satellite, and I don’t have to deal with any of the cloud cover issues that you’re gonna have when you’re dealing with satellite imagery.

Ariel: One really interesting thing, I just wrote about this, and it’s fascinating. So if you look at all the satellite imagery that’s generated on a daily basis across the world, it’s roughly 300 to 400 terabytes of satellite imagery per day. But if you look at all of the content that is coming from kind of all these next-generation sensors, I refer to them as VLR so that is video lidar radar. That is roughly today 200,000 terabytes per day.

Daniel: [inaudible 00:14:21]

Ariel: So even if you [crosstalk 00:14:22] say, “Oh jeez, the satellite data order of magnitude is off by five,” right? So let’s increase that to 1,500 terabytes a day, and the order of magnitude of the VLR is off by like 5x right as well. They’re just not even the same ballpark in terms of the amount of content that these new sensors are generating, and lidar hasn’t even been fully deployed, right? Lidar data, as it gets into more and more cars, as radar gets into more and more cars, as video gets into more and more cars, is gonna fundamentally change those numbers in dramatic ways.

Daniel: Yeah. I totally agree. Like the amount of data being produced sounds incredible, but I guess it also … What do we do with that data? Like today, remember five years ago we all ran around talking about big data and how it was gonna change the world? And then most organizations found out they were just drowned in data. They collected everything they could and ended up drowning in it and couldn’t do anything with it.

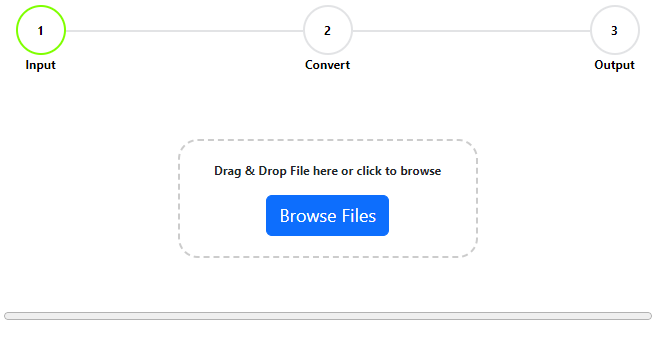

Daniel: So it sounds like you’ve found a way to fixing that. So I’m assuming this process is relatively automatic. I have a drone flying around, or I have a video that I want to get to you guys somehow. How do I do that? Do I send it to you, or can I upload it somewhere, and what’s the process after that in terms of until I can see it on a map?

Ariel: Yeah. So great question. So the simple way is you just drag and drop those video files into Hivemapper. So you go to Hivemapper.com, you just upload. You go “upload videos,” you know kind of very similar to Dropbox. You take all the video files that you want. If there’s attached metadata files, you put those in there as well, and then you just hit upload, and then you [inaudible 00:16:02].

Ariel: And so then you come back 45 minutes to an hour later, and you have a new refreshed map with all the change detections visualized for you for that specific area that we mapped for you. And we’ll automatically … So there’s nothing that you as a user need to do other than just wait 45 minutes. So we’ll automatically say, “Okay, you gave us 30 minutes of video. We were able to actually map roughly 15 minutes of it. Here are the results. Oh, by the way, the other 15 minutes, it failed, and here’s why it failed.”And so we’ll also give you feedback in terms of for that next time around, here are the reasons that this specific part of the video failed.

Ariel: And so that’s fundamentally the process. For some of our larger customers, they do what’s referred to as bulk video upload where they just point Hivemapper at a directory where they’re automatically dropping all the video that they’re generating, and then Hivemapper is just continuously looking for any new files in that directory, and then we just automatically load them.

Daniel: And how do you deliver that data back to the customer? How do I see it again? Is it a web service that I can drag into my existing DIS, or is Hivemapper, is it a platform? Is it an online platform?

Ariel: It’s an online web-based platform. So you just go to Hivemapper. Once you create your account then it simply like … You go to Hivemapper.com, and you access all of your maps as well as all the visualization for the maps, all the change detection in a web browser. So there’s no additional software client that you then need to go download to be able to do it, and so we really try to provide an all in one experience from the actual map engine that produces the map to the map itself and all of the interface and all the features that you need to visualize and analyze your map.

Daniel: A lot of organizations don’t want to give their data away. So is there room for … like in Hivemapper on the web platform there, the web-based client, is there room to drag in a service that I had from my own organization, but I don’t really wanna make it public? Or deliver that data to you?

Ariel: Yeah so there’s … We go even one step further. So if you really want to make all of your data private, we provide Hivemapper Colony which is a product of ours which is entirely self-hosted. That means if you’re actually downloading the software, installing it on your own servers that are run within your organization. So if you’re extremely sensitive to this video, this map data that I’m generating is so proprietary, so classified that nobody else can see it, then you can run Hivemapper entirely disconnected from the internet. So that’s Hivemapper Colony.

Ariel: If you can use a cloud-based product, a SAS-based product, then you can upload your video like we were describing before, use Hivemapper in a totally private context. So that would be akin to saying like, “Hey, I’m gonna sign up for Salesforce and put all my customers and leads and opportunities and contacts into Salesforce.” Obviously, no other business is gonna have access to that other than you. And so that works very similarly with our cloud-based product.

Ariel: And then the third option is like, hey, I am the state of California Offices of Emergency Services, and it’s actually really helpful as I create those maps to educate the citizens of California on what’s happening as I’m fighting these fires, as I’m dealing with mudslides in Santa Barbara, I’m mapping, and I’m learning about what’s happening in these cities and how these cities are being impacted by these natural disasters, but as I create these maps that are fresh and that visualize these changes that are occurring, it’s actually really helpful for the constituents and the citizens of Santa Barbara to be able to see that.

Ariel: And so they want to make those maps public.

Daniel: Absolutely. Absolutely. You mention a few interesting things there. Right at the start, we talked a little bit about change detection, and as soon as you said that I thought, “This would be fantastic for hazard mapping.” You know, those situations where you need to process data, you need to get that overview fast, and you need to be able to update it. With drones and video and Hivemapper, it sounds like you’ve got a really good solution there.

Daniel: Is hazard mapping like the primary focus of this technology?

Ariel: I wouldn’t say that use case is the primary focus. So we refer to it as damage assessment. It’s fundamentally same idea. Right, hazards. But so the first responder market that is dealing oftentimes with these natural disasters where the earth is constantly changing and as we’re dealing with climate change, that, unfortunately, is becoming a bigger and bigger problem for us.

Ariel: And so absolutely. The ability to understand if I’m fighting a fire, if I’m dealing with mudslides or an earthquake, and I’m a first responder, I gotta understand very very quickly the extent of the damages. Because once I understand the extent of the damages then I can make resources allocation decisions, right? Or I can like request more budget for actually dealing with that, but I gotta know. Is there 100 residential partials that have been entirely damaged, or are there 500?

Ariel: And today, that process of collecting and verifying that information and then being able to go to the government or the president or whoever and saying, “I need an additional billion dollars because here’s the extent of the damage.” You need data to stand on. You can’t just make these numbers up and request budget against that.

Ariel: So getting that information quickly and making sure that it’s accurate information is critical to making those budget requests to deal with these hazards and these natural disasters. And so that’s really where Hivemapper comes in and helps. That’s for starters.

Ariel: Then the second part of it is, “Okay, now I’ve got the money, I’ve got the resources to deal with this problem. Where do I put that?” Right? Is that road to that piece of critical infrastructure, is that road still accessible, or has it been damaged? All my critical infrastructure, what is the extent of the damage? You know, showing somebody an image of a before and after and then saying, “Hey go figure out whether or not there’s any damages,” very very time-consuming.

Ariel: And so there’s a way now that we can automate that where we can automatically discover the changes and really help these analysts and these people who are looking for this to hone in on where are the real problems rather than just saying, “Go. Here’s a map of the before, and here’s a map of the after. Figure it out.”

Daniel: Yeah, absolutely. I mean those all sound like really really good use cases for a technology like this. What about some of the other use cases that you mentioned? You said that maybe this wasn’t the primary focus of Hivemapper?

Ariel: So I think on the defense world, I think that’s where frankly was not the initial focus of Hivemapper, but they came knocking on our doors and said, “Listen, you know, we are huge … A, we have a ton of video, right? And so we have aircraft that are flying around. We have drones that are flying around. And we don’t use this video very well today. And so how can we actually make better decisions, separate good guys from bad guys, and do that in a much more efficient way and in a much more precise way, right? We don’t want to hurt the good guys. We want to just focus in on the bad guys here. How can we do that and do that faster and more efficiently and more safely?”

Ariel: And so they came to us saying, “Hey, there’s a really interesting use case here for what you guys have built. We would like to dig in with you to use your software to help us with that.” And so that was a use case where it really opened our eyes to in the gov-defense world, intelligence world, they are very lean in forward when it comes to geospatial technologies. So I don’t know if you know the history of Google Earth, but Google Earth prior to it being Google Earth was actually an acquisition that Google made of a product by the name of Keyhole.

Ariel: And Keyhole was kind of the … It is what Google Earth is today, but many of its early customers were in kind of the gov-intelligence world. You know was used pretty heavily around the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War to really help them visualize kind of what was happening. And so it’s a great example of kind of this new technology that ultimately found kind of a very large vertical for itself in the gov and kind of intelligence world.

Daniel: I do actually remember that. I remember … Wasn’t that where KML came from, the Keyhole Markup Language, or something like that.

Ariel: Exactly.

Daniel: When you’re talking there, I wondered too if something like this couldn’t be very useful in terms of making maps for machines. Base maps for autonomous vehicles. I mean if you’re talking change detection, in my mind anyway, autonomous vehicles will have some kind of base map that they navigate after, and then they’ll, of course, have their own sort of navigation systems and make decisions on the fly. But having that base map would really speed up the process, I think.

Ariel: No, absolutely. So today we focus a lot of our work on autonomy. Supporting autonomous systems that are aircraft based, right? Drones and so forth. That’s kind of version one of it, and the reason for that is because currently, Hivemapper builds maps at roughly 30cm absolute accuracy. And so that is by far more than enough for the world of autonomous aircraft. In the world of ground-based vehicles, we would need to dramatically improve our absolute accuracy and get it down to sub 5cm to be very very relevant in that world.

Ariel: So there’s additional products and technologies that we would have to do to support autonomous vehicles. It hasn’t been a focus of ours, frankly. For a lot of reasons. One is there’s a ton of people who are trying to crack that market. And in my view, it’s still on the earlyish side in terms of getting in and there’s probably like, right now, ten customers that you could realistically sell mapping technology to in the autonomous vehicle world. Maybe 30, right. But the number of customers that you actually have that could write meaningful checks to you is not huge.

Ariel: You know, that will change ultimately as more and more things become autonomous in the world, I expect those numbers to grow pretty significantly, but as of right now I think we’re very much focused on business organizations who need/require fresh geospatial data, and so those exist across local cities, states, federal governments, oil and gas, real estate, construction. There’s just like a ton of verticles that can leverage this data.

Ariel: Which gets me to another point which is I think we as an industry haven’t done a great job in terms of serving business users, professional users. Like if you go into most organizations today that use a tool like [s-ray 00:27:58]. There’s like okay, here’s my GIS people. There’s five, maybe ten of those folks in some of these larger organizations and they’re your GIS specialists.

Ariel: But it seems silly, right? So you go to them, and you’re like, “Hey, I have this question.” Then they go away for two or three or four days, and then they come back, and they try to give you some data that they’ve crunched using the s-ray tool or some other geospatial technologies. That just seems crazy to me because the amount of data that exists out there that’s geospatial in nature that these users could have access to that they could leverage on a daily basis is tremendous.

Ariel: And so the idea that there’s this gatekeeper of these GIS specialist folks that need to kind of divvy out the data to individual users seems like a huge missed opportunity for us as an industry. Like today if I want marketing analytics, whether in sales or business operations or there’s plenty of SAS-based tools out there that will tell me and give me a good understanding of what’s happening with our marketing analytics.

Ariel: I don’t have to go to a specialist to get all of this data. So we want to break down, help break down, some of these walls to just make this data more accessible to more people within these organizations.

Daniel: Yeah, and I agree with you on a lot of what you said there, and I think you make some really good points about the geospatial industry. So how do you see this going as an industry, then? Geospatial, what are we talking about? Are we gonna break it down so much that we’re gonna talk about the end of that sort of GIS group and organizations? The end of the specialist in house? Are we talking about sort of drag and drop services that sort of fed into any old visualization software?

Ariel: Yeah, so I think there’s two really important things. There’s probably a couple really important things that are creating fertile ground for us to rethink how we deliver geospatial information to the enterprise. So one is I think we covered it which is all these VLR sensors, right? Video, lidar, radar that are just out there in the world.

Ariel: So for example, if you’re a facilities manager of a campus, you could put for example dash cam video cameras on all of your cars, all of your trucks, etc that are driving around the campus on a daily basis. All that video can then be ingested into a tool like Hivemapper and put to use, right? What I mean put to use it’s like what’s going on, right? Is the awning on this building leaning? Is the flagpole on this area, is that broken? Is the parking meters over here, did somebody knock into it and it’s destroyed, right? All of this information can be fed into a tool like Hivemapper, and it’s just being passively collected and processed so that the facilities manager can start to prioritize here’s all the issues that are occurring in and around my campus.

Ariel: But here’s the thing. I think the other thing is is that users don’t need pretty maps, and pretty maps … I think we’ve gotten as an industry, addicted to pretty maps. And pretty maps are awesome, right? We all love staring at them, but we all love staring at them for like five minutes, if that, right? We’re like, “Oh my god, that’s beautiful. That’s gorgeous. It’s eye candy.” And so what? And so I think if we can get away from thinking of maps as purely these beautiful things, which they definitely are, but refocus the conversation to say, “No, no, no really the important bits of information that you’re gonna extract from a map are presented to you almost in a spreadsheet form where you can go through and say, ‘Hey, this stop sign in this part of your campus, somebody ran into it. The awning over here was detected that it was leaning or falling, and that happened over here yesterday.'”

Ariel: And so you can almost get a spreadsheet of all the potential issues that you’re dealing with as a facilities manager and then you can start to make decisions and start to prioritize against that spreadsheet. The fact that it was all derived because you have these sensors and you have this mapping technology is almost beside the point, right? But ultimately the things the end users are actually comfortable with is like work orders and spreadsheets. Not pretty maps.

Daniel: That’s a really interesting way of looking at it, I think, because the mapping industry is sort of based on that idea that visualization of data is better. It makes it more accessible to people. And what you’re saying is you’re going the other way now, and I think that’s a really interesting thought because in some ways you’re absolutely right. I mean, beautiful perfectly visualized maps, perfectly visualized data you can’t really use it for very much. You know what I mean? You can’t plug it into your spreadsheet. You can’t put it into another system as it’s just for people. It’s just for that visual effect.

Daniel: So that’s a really interesting thought that that is gonna turn on its head now, and we’re gonna go the other way. And we’re way more interested in getting an answer. Don’t show me the map. Just show me the answer.

Ariel: Yeah. The only reason you can do that, by the way, now since that’s a new … is because of machine learning capabilities. You couldn’t do that eight years ago. And so that’s the thing that’s been changing is the underlying technology to do this type of stuff now exists whereas most of the other mapping companies were dealing with a different set of technology tools that were available to them.

Ariel: So they obviously prioritized things like visualization. So I think that made sense in its time.

Daniel: But do you think is it the technology that’s slowed us down, or is it the culture around mapping? Is it the understanding that okay … maybe not a wee while ago, but ten years ago there was this saying like, “Spacial is special.” I mean this is something different. We need to treat this differently. And do you think is it … So my question is, again, is it the technology that’s held us back, or is it that sort of understanding of that this spacial data, this mapping data, is somehow different from every other kind of data?

Ariel: I definitely think it’s … You know maps were always, like even when they were in their physical form, these things that you opened up and that you looked at, right, and they were very … Some of those physical maps are incredibly gorgeous, and so I think that was the starting point for maps. And then it carried over into the digital world, and we just made those maps even prettier. We made them … They have all these graphics on them with things moving, and so it’s like it created that oo and that ah moment, and so I do think that yeah, there’s a culture of creators that are always looking for that positive feedback.

Ariel: And so when you are doing a demo or creating something on a website or whatever, and you put out a beautiful map, you’re gonna get those oos and the ahs and the reshares and all that kind of stuff. And so that is part of that feeding cycle that encourages more of that. So I do think culturally, it’s gonna force us to take a step back and be like, “Well, maybe that’s not actually the most useful thing,” as we started to think about getting this data into the hands of not, you know, ten percent of Enterprise users, but in the hands of 75% of enterprise users.

Ariel: And that … to get from 10% to 75% of Enterprise users is gonna require us to take a different approach and a … And so I don’t think we can continue to do the same thing over and over. And we’ve probably beaten that horse to death in terms of pretty visualizations.

Ariel: In terms of the technology, yeah I do think that there was a technology limitation there for sure. In terms of being able to extract this data at scale that’s really meaningful and relevant, I don’t think that technology was very good or it exists or it was even financially viable to get at that just because of the processing and you compute requirements.

Ariel: So yeah, I do think there was also a technology limitation there for sure.

Daniel: If we could just stay on the subject of that sort of, the GIS gatekeeper, just for a second. If I was going to university now, really interested in geography, GIS, and wanted to go down that path, what kind of advice would you give me?

Ariel: I would actually go down the path of … So I think there are two parts to this. I would get deep into things like machine learning and machine division technology. So very computer science heavy focused. Then the other part of it is design. And designed thinking. Because this goes back to trying to get us out of just thinking of maps as pure visualizations and starting to think of them as almost something else.

Ariel: And I think if we can force the younger generation to kind of rethink even the core metaphors or underlying objects of what constitutes a map, I think we’re gonna be able to push mapping technology further and further ahead.

Ariel: And so that are the two disciplines that I would focus on. And you know, depending upon your personality, you may lean towards one more versus the other, but I think both of those things are required to really build the next generation of mapping and geospatial products.

Daniel: Thanks very much for your thoughts on that, by the way. I really appreciate that. It’s always interesting to hear other people’s opinions. And I have to admit I agree. I think if we’re gonna do this at scale, we’re not just gonna be able to sit and choose the tools one by one in [Isry 00:37:56] for example and [inaudible 00:37:57]. That’s not gonna happen. We need something else. If we could just come back to this idea of data collection, again, if that’s alright with you. I find that I’m really fascinated by the idea of using video. But we also talked about using lidar. We talked about using radar.

Daniel: Now in the last few years we’ve seen an incredible leap forward in terms of what a camera, even on a cellphone, can do, and I’m assuming in terms of what drone cameras can do now. Like I’m assuming that technology is moving even faster. Are we gonna get to the point, in terms of mapping, the kind of mapping that you’re doing and the kind of mapping we’re gonna need to do at scale if this is gonna work where we’re just gonna jump right over lidar and radar. Where they’re not gonna be used anymore. Are they gonna be seen as an old mapping technology soon?

Ariel: That’s a good question. It depends who you ask. So the advantage of video cameras is that they’re ubiquitous. They have the color. So I just got a new car, and it has this amazing front facing and back facing camera, and I’m just curious … I fundamentally just don’t know yet like where all that video goes. Is it destroyed? Is it sent back to the car manufacturer? But that video that exists on my car is extraordinarily valuable.

Ariel: And so being able to ingest all of that and build maps from that would be extraordinary as well. But getting to your question of … No, I don’t think that lidar is going … I don’t think we’re gonna skip over lidar is the short answer. I think lidar is gonna get cheaper. I think it’s gonna get deployed into millions upon millions of cars. That seems pretty inevitable to me. And there’s advantages of lidar over a camera. I think it operates in many different kinds of environments. The precision and the accuracy of it today, at least, is significant.

Ariel: It can cut through vegetation, unlike a car. So if you’re dealing with roads or even collecting from above and you’re in very dense vegetation areas, the technology as it exists today for a video camera is just not gonna be as effective as building maps from lidar. So there’s a lot of advantages of lidar where I don’t think we’re gonna skip over that any time soon.

Daniel: I tend to agree. I think, anyway, in terms of data collection the future is like multichannel. I don’t think it’s just one thing. I think people are gonna have to focus more and more on all the different available channels in terms of data collection.

Daniel: Then, for me anyway, the question becomes more, “How can we make them work together?”

Ariel: Yeah. That’s exactly it, and like so we … Like any time you upload a video to Hivemapper, just going back to the whole like how does Hivemapper work thing, you upload video, we are automatically pulling in all available lidar that we have for that area because we want to combine the maps that we create from the video with existing lidar that we already have for that specific area, and by the way there’s been a ton of lidar collections throughout the US, throughout Europe, throughout many parts of the world. This lidar data exists. We’ve aggregated a ton, ton of it. Such that we can combine lidar data with your video or with the maps that you generate from your videos into one single map.

Ariel: And so I agree. It’s never gonna be an either or. From a customer perspective, that’s not what you want. From a customer perspective, it’s like if there’s great lidar data there, then and it’s gonna help me get to a faster, better answer great. Use it, right? If there’s great radar data there, great use it.

Ariel: So I just don’t think the customer is religious about this stuff. They’re just like, “I need a freaking answer to my question.”

Daniel: Yeah. I completely agree, and I can’t imagine them caring. They’re like, “Just give me the best answer. Thank you. Don’t bore me with the details. Just do the thing.”

Ariel: Yeah, I remember talking to this one customer, and he’s like … it was so clear to him that he just did not care at all about how the technology worked, and I was like it was somewhat refreshing because we’re, as mapping technologists, designers, we think about this stuff all day long. But from his perspective, he had like fifteen minutes to talk to me, and he’s like, “Here’s what I need. I don’t care. Just go get it, right?”

Daniel: Fair enough. Why bog yourself down on the details. That’s fair enough. And the thing is, I guess, people were paying you that, “Go, be the expert. Do the thing. Give me the answer.” I know we’re coming to the end of our time together. Just before we say goodbye, can you tell me, what is the future of Hivemapper? We’ve talked about a lot of things around the geospatial industry, but if we go back to Hivemapper, like specifically, where are you gonna be in two years or five years? What are we gonna see from you guys?

Ariel: Yeah so going back to that transition from satellite imagery to these VLR sensors, we’re at the very very beginning of that. To steal a line from Jeff Bezos, like it definitely feels like very much like day one, and I can say that with a straight face unlike eCommerce or something like that, right?

Ariel: Yeah, it feels very much like day one, and I think what we’ve seen is that over the last … If I would’ve started this company five years ago, it would’ve been super slow in the early days, and now we’re seeing that it’s picking up. And the reason that it’s picking up is because all of this data that exists on video cameras, on this lidar data, is looking for our home. Today it’s not used, and the customers are like, “I collected this data. I know there are better uses for it.”

Ariel: If you show up and you show them the uses for this data that oftentimes they’ve already collected, or are collecting, that’s a win. That’s a big win for them. But you do need to match them and spend the time and show them like here’s how all this data that you already have or are collecting can actually be useful in the context of a map and more importantly with answers to your specific information.

Ariel: So where do we want to be in two, three, four, five years from now is we want to be in a situation where we are the predominant place where all of this data goes, and where tens of thousands of organizations are getting answers to their questions on a daily basis and running their cities better, running the organizations better as a result of getting all this data fresh delivered to them on an hourly, if not 20 minutes, basis.

Daniel: Amazing. Sounds like a bright future. Hey, just before we say goodbye, where can we go to learn more about you?

Ariel: Head over to Hivemapper.com. So hive as in a beehive. And then mapper. Hivemapper.com, and there’s a ton of stuff out there. Ton of blogs. Contact us if you have questions. We’d love to hear from folks out there in terms of things that they’re doing in this world.

Daniel: Fantastic, and I’ll be sure to link all that up in the show notes so people can find you from there. Ariel, thank you so much for coming along today and talking to me. I really appreciate it.

Ariel: Appreciate it.

Daniel: Well that’s the end of the interview. Thank you so much for listening. Personally, I really enjoyed talking to Ariel. I thought he had some really interesting ideas on the geospatial industry and where we were going and what it was gonna take to get there. I also really enjoyed hearing about Hivemapper. I think it’s an incredibly interesting technology that he’s built there. And I can see a lot of different use cases for it.

Daniel: A transcript of this podcast will be available at MapScaping.com/blogs/podcast. You’re also more than welcome to reach out to us at Mapscaping. You can find us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Or email us at info@MapScaping.com.

Daniel: Thanks so much for listening. We’ll have a new podcast for you soon.